Scriptwriting: How To Write Killer Dialogue

Scriptwriting: How To Write Killer Dialogue

As we all know, the name of the game is to write a script so good that anyone who reads it says "this guy/gal's got it!" Many times, the dialogue in a script can be the one thing that makes people want to champion your work. The best example being Juno, which got accepted into the Sundance Screenwriter's program and later turned into a movie based on the strength (and arguably the originality) of the dialogue.

The action lines were serviceable, and the story was fine, but the dialogue...whoa. When the Sundance list hit agent and manager's inboxes and Juno first started getting passed around, you would have thought no one in Hollywood had ever read great dialogue until Diablo Cody slapped them upside the head with it. Looking back, it was absolutely ridiculous the hyperbole being thrown around but at the end of the day, her voice was so strong and the dialogue so interesting, and yes, full of subtext, that dialogue alone landed her a big career.

So what are the different aspects you need to integrate into your dialogue to make it pop? First, let's touch on some basics:

1. Too Much Dialogue

A script is not a play. Your goal is NOT to have dialogue that looks like a bunch of monologues. Try to keep 95% of your dialogue to 3 lines or less on the page. Clever dialogue is found in quick back and forth exchanges, not prose-y speeches. Think about one of the best screenwriters known for his dialogue – Aaron Sorkin. Have you ever watched a scene from The West Wing? Click here for an example.

Now, it's not perfect by any stretch, but it illustrates the point that if you keep it snappy, it keeps it moving. And a fast moving script, like a fast moving story, is entertaining and sometimes it can move so fast that you don't have time to realize whether it's great quality or not. You just know you're entertained. So, use it to your advantage. Keep the dialogue short, quick back and forths, and you'll reveal plot and character just as quickly.

Now, a side point I want to make about this, and what Sorkin does so well in one of my other favorite shows, Sports Night, is he uses quick back and forths to set up a brilliant monologue. You don't get a whole bunch of monologues during the course of one show, but you get one that really sticks you in the gut. And THAT is how you use a monologue like a pro. Here is one of my favorite scenes in the entire series. It's also not perfect, and the first season of Sports Night was just getting some footing and the laugh track was horrible, but it should illustrate my point.

2. Lack of Subtext

We've all heard the word. We know what it means. And yet it is the most common reason for bad dialogue. The absolute number one mark of an amateur is dialogue that lacks subtext. Subtext is when a character says something and we (the reader or audience) can tell or know that there is something behind the words of what is being said. For example, let's take a protagonist we know is hurting from a break up, and he runs into his ex on the street:

EX-GIRLFRIEND

The weather's pretty nice today.

PROTAGONIST

Seems kind of cold to me.

Now, it's not the world's best writing. But you get my example. We, the reader, know there's something behind the protagonist's words. He's making a dig at his ex, and referencing their break-up...all while on the surface talking about the weather. That's subtext.

When it comes to dialogue and subtext, never ever have a character come out and say what he is thinking or feeling. Brilliant characters have us discover/uncover what's going on inside their heads by their actions, or how they dance around important topics when they're talking...not how they address them head on.

Here is an example of what I'm talking about in a script by Allan Loeb called Only Living Boy In New York.

Now, say what you will about Loeb's produced movies, but his scripts are excellent reads and this script, along with Things We Lost in the Fire were low concept indie scripts that got him big writing assignments and truly launched his career. This script in particular has long been on lists of "the best unproduced scripts" and has been in development for a while. Now, onto what you should notice from the script...

First, it's obvious that Thomas is hopelessly and totally in love with Mimi from the get go, and if you read the entire story the art gallery scene not only does a fantastic job setting up the whole movie, but it sets up the theme brilliantly as well. Notice how the characters dance around the elephant in the room for as long as possible...and then BAM! Thomas is forced to bring the elephant into play (that they slept together). Even when Thomas is laying out on the table, he's not really laying it out on the table. We know he's hopelessly and deeply in love with her but does he ever say it? NO. And we can tell from Mimi's opening line and subsequent dialogue that she knows he's hopelessly in love with her but she never addresses it head on. She uses the critique of the art piece they are looking at to circumvent actually having to SAY what she's really thinking. This scene is full of all kinds of other subtext, but you get the drift.

3. Characters All Sounding the Same

Now, another common culprit that keeps writers from making their work studio quality material is characters that sound exactly alike. Remember, each character in your script is a living, breathing, thinking person with different wants, needs, and point of view from the others.

A good exercise to fleshing out characters is to figure out what each character's super objective is. It sounds like a hokey term, but in essence you figure out what a character truly wants in life (not necessarily in the story). These are the big things, the ones in our very core...to love, to be loved, to be powerful, to be respected, etc.

Once you figure that out, realize that this is JUST to determine their core character...how they approach every situation and character they encounter during the course of your story. It's the foundation, and while it's certainly the most important layer, there are more layers: the style, and the details.

A character's style is not about their fashion, but about how, knowing their core, they approach life and other people. Things like humor, vanity, selfishness, selflessness, etc. You can think of a character's style as a collection of their coping and defense mechanisms. How they get by on their day to day life.

The details are how, knowing their core and their style, what little actions they take frequently. For instance, if he drinks a lot, or is always fixing his hair or keeps a pack of cigarettes rolled up in his sleeve...even though he never actually smokes. Each person has their own unique tics and as they say the devil is in the details. Well, the character is right there with El Diablo (call back!) as well.

So to finish up what you need to notice about the Only Living Boy in New York script, between the character's roundabout way of parsing out information, their distinct voices from each other (stemming from different wants), and the dialogue feeding into the theme...each of those individually are subtext, but the fact that all three are present clues the reader in that the writer is a professional.

4. Word Pictures / Visuals Within the Dialogue

As you know, great action lines have visuals that pop and succinct word pictures. Things that when we read it, we can quickly and easily see it in our minds.

It's the difference between:

A. The notebook gets passed over the table

B. The bulging notebook slides across the table

When talking about action lines, it's obvious why and how to integrate word pictures. But what about dialogue?

Well, obviously if a character is speaking ABOUT something, if they can say it in a visual fashion, the audience will be able to quick and easier see (and depending on how good you are) and feel it in their own heads. Here is another example from Sports Night (I'm a Sports Night machine, I know).

Notice how he describes how his brother was a genius (the kit he built) and also "you deserved better in my hands" (which is a nice use of a metaphorical word picture), notice how we can see in our heads what must have happened that fateful night he ran a red light. THIS is visual dialogue.

5. Leaving the Obvious Out

I?m not going to get too deep into this, as it?s pretty self explanatory and most of you are already doing this well. Basically, another aspect of great dialogue is about leaving the obvious out. This does go hand in hand with subtext, but it comes at it from a different angle. On its most basic level, it?s when we as an audience are expecting a character to say something? and then they dont. Maybe they give a look, or say something else, or don?t say anything at all, but we get it anyway. An easy example would be if we?re in a romantic scene, and we are expecting the Protagonist to finally(!) say ?I love you.? But instead, he looks deep in her (or his) eyes and:

PROTAGONIST

I want you to know-

LOVE INTEREST

I know. You too.

They kiss deeply.

So, that's leaving the obvious out. An extension of that is (drum roll...)

6. Changing the Obvious Up

This one is pretty self explanatory, but it's about taking the audience expectations and turning them on it's head. For instance, if a female protagonist were to ask a male protagonist for his hand in marriage. While it's the 21st century, this hasn't been done too often in movies or TV yet, so it's unexpected.

Lastly, we have one of Sorkin's (and my) favorites:

7. Call Backs

When a character references something that was said earlier, either by themselves or another character, it's a call back. Sorkin's work is full of this, as is Mamet's and others. It's usually used as a way to inject humor, but it can definitely be used for dramatic effect as well. In the Sports Night clip earlier, Dana said "You're ruining my show" when she walked into Dan's office, and then again when she left. That's a call back.

Now, here's a script that features call backs, changing the obvious up, leaving the obvious out, and a whole host of other things we've highlighted in this article. Ready, here we go.

Now, this scene is about Ben going home with his girlfriend to meet her family. It's the type of scene we've seen many times before, usually played for comedy. Except these pages takes the Meet the Parents set up and turns it into a subtle, beautiful, realistic situation. My favorite moment in these pages is when Ben does a call back to Olivia's "I did the math." That moment is brilliant because not only is it a nice call back for the audience, but the fact that Ben uses it makes this little girl he's trying to befriend totally go all-in to Ben's camp. The part where we realize the father is going to accept him when he gives him the glove his father gave him leaves out the obvious...he doesn't actually tell Ben he likes him or that he is glad he's his daughter's boyfriend. He doesn't have to because of the ACTION he took. Instead, he just says "welcome to the family" ...but that line has so much more meaning BECAUSE he didnt come out and praise Ben. How this scene plays out really speaks to "changing the obvious" as we've seen this set up before so many times...played for broad comedy...that it's refreshing to see it played softly.

I'm not saying these are perfect pages (it's from a rough draft of one of my favorite writer's passion projects), but they do a great job illustrating the last three points I wanted to make.

The action lines were serviceable, and the story was fine, but the dialogue...whoa. When the Sundance list hit agent and manager's inboxes and Juno first started getting passed around, you would have thought no one in Hollywood had ever read great dialogue until Diablo Cody slapped them upside the head with it. Looking back, it was absolutely ridiculous the hyperbole being thrown around but at the end of the day, her voice was so strong and the dialogue so interesting, and yes, full of subtext, that dialogue alone landed her a big career.

So what are the different aspects you need to integrate into your dialogue to make it pop? First, let's touch on some basics:

1. Too Much Dialogue

A script is not a play. Your goal is NOT to have dialogue that looks like a bunch of monologues. Try to keep 95% of your dialogue to 3 lines or less on the page. Clever dialogue is found in quick back and forth exchanges, not prose-y speeches. Think about one of the best screenwriters known for his dialogue – Aaron Sorkin. Have you ever watched a scene from The West Wing? Click here for an example.

Now, it's not perfect by any stretch, but it illustrates the point that if you keep it snappy, it keeps it moving. And a fast moving script, like a fast moving story, is entertaining and sometimes it can move so fast that you don't have time to realize whether it's great quality or not. You just know you're entertained. So, use it to your advantage. Keep the dialogue short, quick back and forths, and you'll reveal plot and character just as quickly.

Now, a side point I want to make about this, and what Sorkin does so well in one of my other favorite shows, Sports Night, is he uses quick back and forths to set up a brilliant monologue. You don't get a whole bunch of monologues during the course of one show, but you get one that really sticks you in the gut. And THAT is how you use a monologue like a pro. Here is one of my favorite scenes in the entire series. It's also not perfect, and the first season of Sports Night was just getting some footing and the laugh track was horrible, but it should illustrate my point.

2. Lack of Subtext

We've all heard the word. We know what it means. And yet it is the most common reason for bad dialogue. The absolute number one mark of an amateur is dialogue that lacks subtext. Subtext is when a character says something and we (the reader or audience) can tell or know that there is something behind the words of what is being said. For example, let's take a protagonist we know is hurting from a break up, and he runs into his ex on the street:

EX-GIRLFRIEND

The weather's pretty nice today.

PROTAGONIST

Seems kind of cold to me.

Now, it's not the world's best writing. But you get my example. We, the reader, know there's something behind the protagonist's words. He's making a dig at his ex, and referencing their break-up...all while on the surface talking about the weather. That's subtext.

When it comes to dialogue and subtext, never ever have a character come out and say what he is thinking or feeling. Brilliant characters have us discover/uncover what's going on inside their heads by their actions, or how they dance around important topics when they're talking...not how they address them head on.

Here is an example of what I'm talking about in a script by Allan Loeb called Only Living Boy In New York.

Now, say what you will about Loeb's produced movies, but his scripts are excellent reads and this script, along with Things We Lost in the Fire were low concept indie scripts that got him big writing assignments and truly launched his career. This script in particular has long been on lists of "the best unproduced scripts" and has been in development for a while. Now, onto what you should notice from the script...

First, it's obvious that Thomas is hopelessly and totally in love with Mimi from the get go, and if you read the entire story the art gallery scene not only does a fantastic job setting up the whole movie, but it sets up the theme brilliantly as well. Notice how the characters dance around the elephant in the room for as long as possible...and then BAM! Thomas is forced to bring the elephant into play (that they slept together). Even when Thomas is laying out on the table, he's not really laying it out on the table. We know he's hopelessly and deeply in love with her but does he ever say it? NO. And we can tell from Mimi's opening line and subsequent dialogue that she knows he's hopelessly in love with her but she never addresses it head on. She uses the critique of the art piece they are looking at to circumvent actually having to SAY what she's really thinking. This scene is full of all kinds of other subtext, but you get the drift.

3. Characters All Sounding the Same

Now, another common culprit that keeps writers from making their work studio quality material is characters that sound exactly alike. Remember, each character in your script is a living, breathing, thinking person with different wants, needs, and point of view from the others.

A good exercise to fleshing out characters is to figure out what each character's super objective is. It sounds like a hokey term, but in essence you figure out what a character truly wants in life (not necessarily in the story). These are the big things, the ones in our very core...to love, to be loved, to be powerful, to be respected, etc.

Once you figure that out, realize that this is JUST to determine their core character...how they approach every situation and character they encounter during the course of your story. It's the foundation, and while it's certainly the most important layer, there are more layers: the style, and the details.

A character's style is not about their fashion, but about how, knowing their core, they approach life and other people. Things like humor, vanity, selfishness, selflessness, etc. You can think of a character's style as a collection of their coping and defense mechanisms. How they get by on their day to day life.

The details are how, knowing their core and their style, what little actions they take frequently. For instance, if he drinks a lot, or is always fixing his hair or keeps a pack of cigarettes rolled up in his sleeve...even though he never actually smokes. Each person has their own unique tics and as they say the devil is in the details. Well, the character is right there with El Diablo (call back!) as well.

So to finish up what you need to notice about the Only Living Boy in New York script, between the character's roundabout way of parsing out information, their distinct voices from each other (stemming from different wants), and the dialogue feeding into the theme...each of those individually are subtext, but the fact that all three are present clues the reader in that the writer is a professional.

4. Word Pictures / Visuals Within the Dialogue

As you know, great action lines have visuals that pop and succinct word pictures. Things that when we read it, we can quickly and easily see it in our minds.

It's the difference between:

A. The notebook gets passed over the table

B. The bulging notebook slides across the table

When talking about action lines, it's obvious why and how to integrate word pictures. But what about dialogue?

Well, obviously if a character is speaking ABOUT something, if they can say it in a visual fashion, the audience will be able to quick and easier see (and depending on how good you are) and feel it in their own heads. Here is another example from Sports Night (I'm a Sports Night machine, I know).

Notice how he describes how his brother was a genius (the kit he built) and also "you deserved better in my hands" (which is a nice use of a metaphorical word picture), notice how we can see in our heads what must have happened that fateful night he ran a red light. THIS is visual dialogue.

5. Leaving the Obvious Out

I?m not going to get too deep into this, as it?s pretty self explanatory and most of you are already doing this well. Basically, another aspect of great dialogue is about leaving the obvious out. This does go hand in hand with subtext, but it comes at it from a different angle. On its most basic level, it?s when we as an audience are expecting a character to say something? and then they dont. Maybe they give a look, or say something else, or don?t say anything at all, but we get it anyway. An easy example would be if we?re in a romantic scene, and we are expecting the Protagonist to finally(!) say ?I love you.? But instead, he looks deep in her (or his) eyes and:

PROTAGONIST

I want you to know-

LOVE INTEREST

I know. You too.

They kiss deeply.

So, that's leaving the obvious out. An extension of that is (drum roll...)

6. Changing the Obvious Up

This one is pretty self explanatory, but it's about taking the audience expectations and turning them on it's head. For instance, if a female protagonist were to ask a male protagonist for his hand in marriage. While it's the 21st century, this hasn't been done too often in movies or TV yet, so it's unexpected.

Lastly, we have one of Sorkin's (and my) favorites:

7. Call Backs

When a character references something that was said earlier, either by themselves or another character, it's a call back. Sorkin's work is full of this, as is Mamet's and others. It's usually used as a way to inject humor, but it can definitely be used for dramatic effect as well. In the Sports Night clip earlier, Dana said "You're ruining my show" when she walked into Dan's office, and then again when she left. That's a call back.

Now, here's a script that features call backs, changing the obvious up, leaving the obvious out, and a whole host of other things we've highlighted in this article. Ready, here we go.

Now, this scene is about Ben going home with his girlfriend to meet her family. It's the type of scene we've seen many times before, usually played for comedy. Except these pages takes the Meet the Parents set up and turns it into a subtle, beautiful, realistic situation. My favorite moment in these pages is when Ben does a call back to Olivia's "I did the math." That moment is brilliant because not only is it a nice call back for the audience, but the fact that Ben uses it makes this little girl he's trying to befriend totally go all-in to Ben's camp. The part where we realize the father is going to accept him when he gives him the glove his father gave him leaves out the obvious...he doesn't actually tell Ben he likes him or that he is glad he's his daughter's boyfriend. He doesn't have to because of the ACTION he took. Instead, he just says "welcome to the family" ...but that line has so much more meaning BECAUSE he didnt come out and praise Ben. How this scene plays out really speaks to "changing the obvious" as we've seen this set up before so many times...played for broad comedy...that it's refreshing to see it played softly.

I'm not saying these are perfect pages (it's from a rough draft of one of my favorite writer's passion projects), but they do a great job illustrating the last three points I wanted to make.

Script dialogue: if your characters are just talking you’re doing it wrong.

When it comes to how to write great dialogue in a script, most advice tends to be quite vague. For example, you’ll often hear how “script dialogue should…”

• “Propel the story forward”

• “Reveal character and theme”

• “Build conflict and drama”

• “Sound different for each character”

• “Entertain with witty, quotable lines”

• “Never run longer than three lines”

• “Never be on-the-nose”

The first problem here is that, while much of this advice is true, it doesn’t really get to the heart of the problem behind 90 percent of bad screenplay dialogue.

Or how to fix it.

It tells writers to do something specific, like add more conflict or subtext, without looking at the bigger picture that’s causing the lack of conflict or subtext.

Similarly, when writers are told to build conflict, push the story forward and reveal character through dialogue, this encourages the act of writing more dialogue. But this is the heart of the problem: letting characters coast through easy-going conversations.

The biggest problem with dialogue in spec scripts: “shooting the breeze.”

Many screenwriters fall in love with writing dialogue—letting their characters loose to just talk and talk and talk because, well, they have a lot to say. In reality, the skill in writing great script dialogue is knowing when and how to shut characters up.

As you’ve probably heard before, every line of dialogue in a screenplay should be in there for a reason. If not it can be cut. However, this advice can be a tricky thing to adhere to because writers often approach script dialogue as characters “just talking.”

But it isn’t…

Rather, a script’s dialogue should nearly always put the characters under some kind of pressure.

A character’s words should be either hard to say or hard to hear.

What we often see in spec screenplays, however, is the opposite: words that are easy to say and easy to hear.

When characters are continually left to “shoot the breeze” like this—chat in a friendly manner with no real purpose or conflict—the reader loses interest. Often not only in the scene, but in the whole script.

It’s okay to have characters begin a scene by talking in a relaxed, friendly manner, engage in small-talk, order food, etc. But if they continue to talk like this for the entire scene—as in the dialogue examples coming up—then you have a conversation that’s “just talking” rather than pushing the story forward.

A script dialogue audit.

Rather than just being told what your script dialogue should or shouldn’t do, we’ve come up with an exercise that should help you see the problem more clearly in your own screenplay.

And the way to do this is to first see dialogue examples of it in another writer’s. The exercise is divided into three parts:

• Read three examples from spec of “shooting the breeze” dialogue

• Discover the kind of fundamental questions you should ask yourself about the dialogue in a scene (which you’ll find after each dialogue example)

• Read your own script and apply the same questions to every conversation

Doing this will hopefully enable you to better identify the problem of chatty screenplay dialogue in your own work and then give you the tools to either rework the scene or cut it altogether.

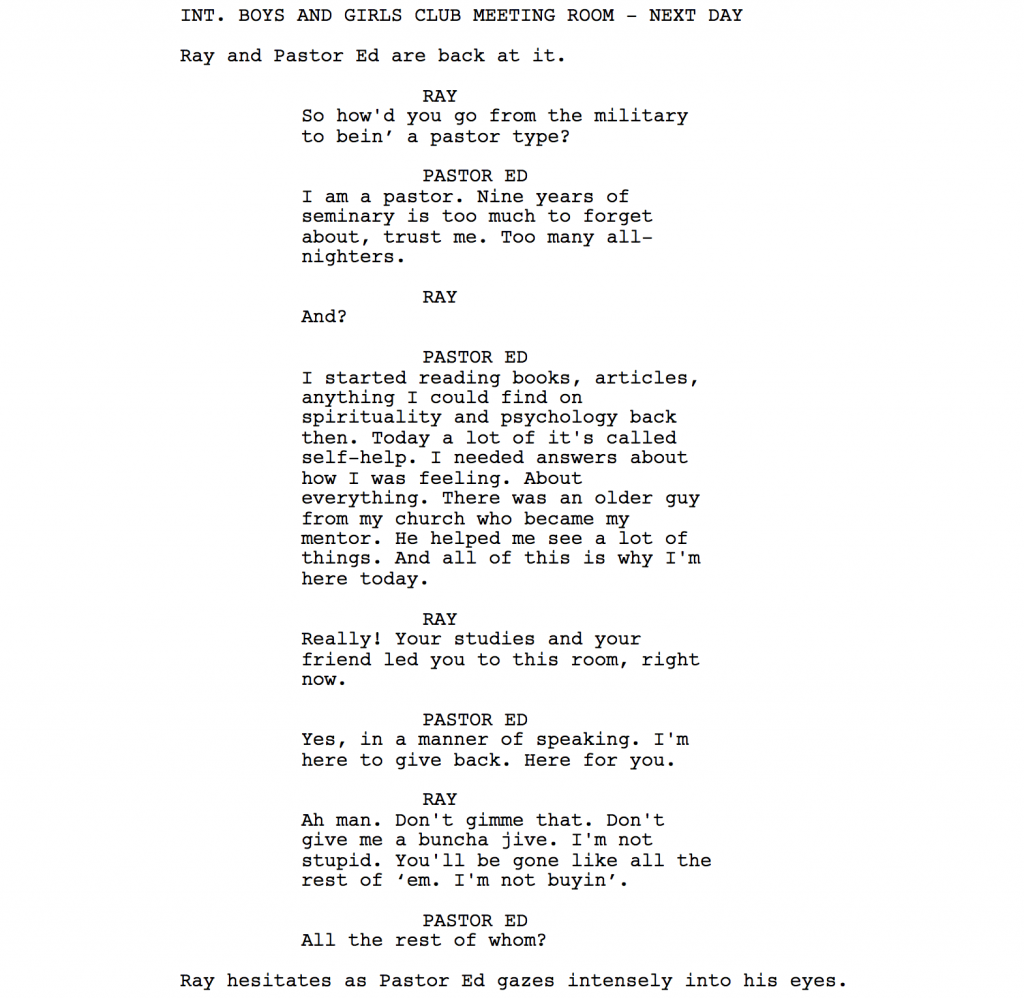

Spec script dialogue example #1.

Now ask yourself the following five questions about the above script dialogue example:

1. Is this a hard conversation for one or both of these characters to have?

2. Does it put one or both of the characters under pressure?

3. Does the conversation involve conflict as one character tries to “win a battle”?

4. Were you engaged and excited while reading this screenplay dialogue?

5. Has a fundamental shift in the story occurred by the end of the scene?

The answer to each of these questions is no.

What’s wrong with this dialogue?

Neither Pastor Ed or Ray are feeling particularly uncomfortable during this script dialogue. Despite addressing difficult subject matter, the tone is friendly and relaxed. Neither Pastor Ed or Ray are attempting to outwit the other in a “verbal battle”—back them into a corner, trick or intimidate, etc.

We have a post here on how to write dialogue between two characters that shows how to inject conflict into a conversation by equating it to a game of tennis.

Note also how both Pastor Ed and Ray’s dialogue also regularly strays over the recommended three lines maximum quota. Read screenplays and watch films, paying particular attention to how much each character actually says all at once.

You’ll find it’s really not much at all.

How to rectify this in your own script’s dialogue.

Go through your own script and make a note of every scene containing dialogue that’s easy-going instead of emotionally charged.

Start with the obvious scenes that should involve verbal conflict but don’t, like the one above between a troubled young man and a pastor. Find these scenes by asking yourself similar questions to the ones above.

If you were in these characters’ shoes, how nervous would you be? How would you struggle during the conversation? How bad (or good) would you feel by the end?

If you’d feel okay then the script dialogue probably needs rewriting to include much more conflict and a “verbal battle” of some kind.

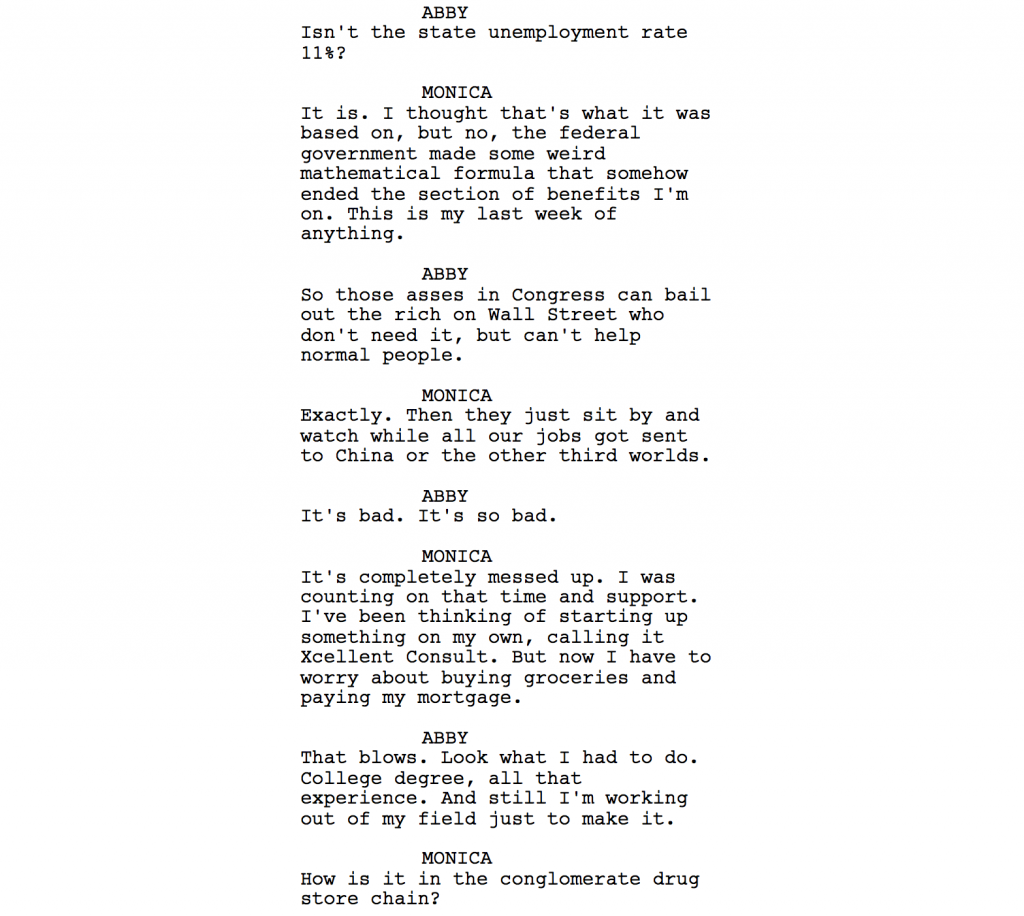

Spec script dialogue example #2.

Now ask yourself these three questions about the script dialogue example above:

1. Is this an important conversation that deserves to be in the script?

2. Does this script dialogue interest, amuse or shock you in some way?

3. Does it feel like a natural conversation between two real people?

Again the answer to these questions is no as it’s another example of characters “shooting the breeze.”

What’s wrong with this dialogue?

Abby and Monica don’t discuss anything particularly important to the story and nothing surprising is revealed at the end to push it forward.

Overall, they spend most of the conversation complaining about the job market, rather than actually putting the other under any kind of real pressure with their dialogue.

Note also the frequent use of questions. Abby asks Monica five questions in the scene:

1. “Any luck finding anything?”

2. “What happened?”

3. “What about the other one?”

4. “Isn’t the state unemployment rate 11%?”

5. “By the way, where’s your friend, Chloe?”

In addition, Monica asks Abby “How is it in the conglomerate drug store chain?”

This Q&A-style of script dialogue is very common in specs and is another symptom of letting characters “just talking” rather than forcing them to use their words as weapons.

When characters are continually asking each other questions like this, it feels unnatural and “on-the-nose” because this isn’t how people talk in real life.

As in the first scene, it’s hard to really imagine Abby and Monica as real flesh-and-blood people because they’re talking in such a direct, obvious way—asking each other straight-up questions for the benefit of the audience rather than themselves.

This also makes the script dialogue uninteresting to read as it feels like the writer is force-feeding us information. There’s no intrigue or surprise here as characters invariably end up answering these sort of questions exactly as we’d expect them to.

How to rectify this in your own script’s dialogue.

Start by going through each scene in your screenplay and noting how many questions are being asked.

If the characters are engaged in a Q&A session, there’s a strong likelihood they’re just amiably chatting and their dialogue is purely for the audience’s benefit.

Seek out banal questions and answers and rework every conversation so the characters are making life difficult for themselves, hiding something, revealing something or engaging in an escalating war of words.

We understand that this can be hard to do as on the one hand screenplay dialogue needs to feel casual and “real,” just like how people talk in real life. On the other hand, dialogue isn’t how people talk in real life at all.

It’s a heightened reality in which characters hardly ever stumble over their words or go off-track, are much wittier than usual and always know just the right thing to say at just the right time.

When it comes to dialogue in a script, every word is selected for a reason, because they want to conceal something, find something out, kiss them, hurt them and so on.

The trick, then, is in making script dialogue feel like real life, but with every single conversation earning its place in the script. And the best indicator is: if the discussion isn’t making the characters uncomfortable or revealing something, it probably needs cutting.

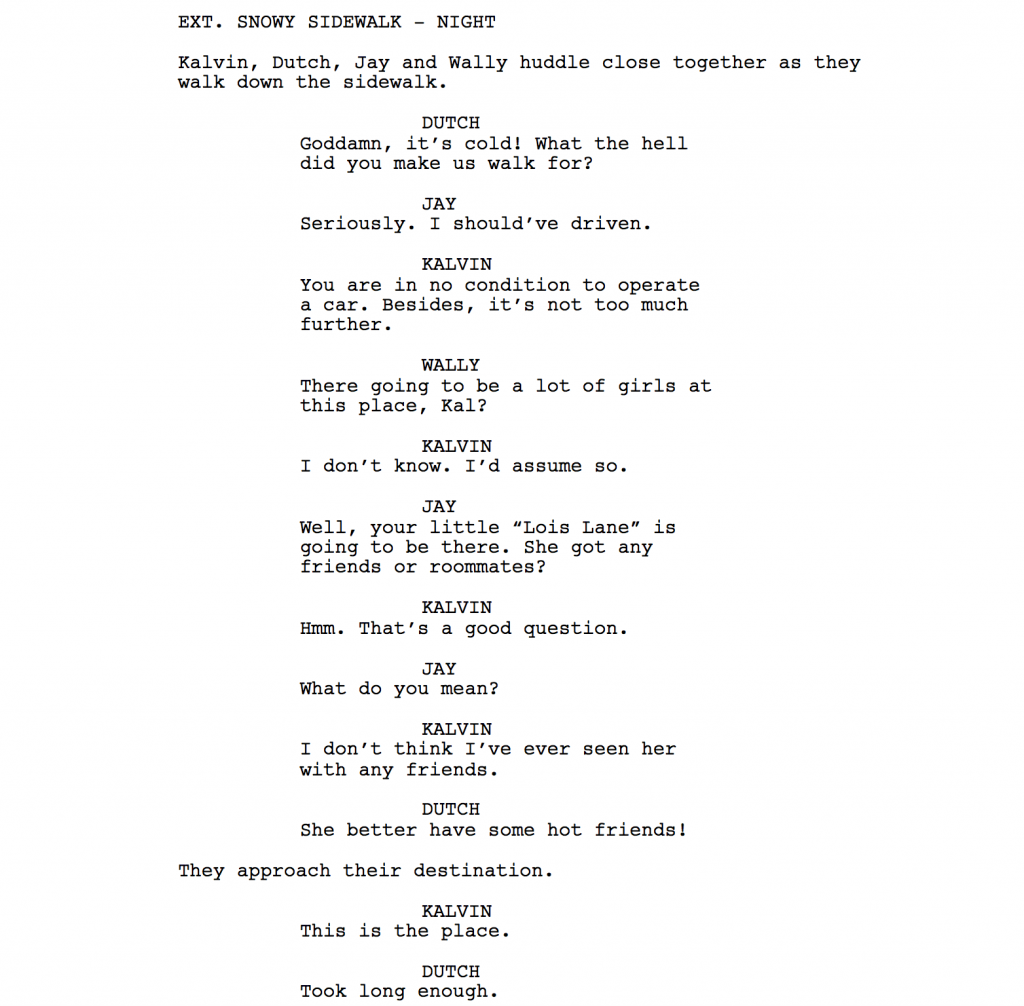

Spec script dialogue example #3.

Here are the final set of three questions to ask yourself about this script dialogue example:

1. Is this a conversation you’ve never heard in a movie before?

2. Does each character have a distinct personality?

3. Does this conversation reveal anything new about these characters?

As you can see the answer again to these questions is no.

What’s wrong with this dialogue?

This dialogue feels uninspiring and generic because yet again these guys are just “shooting the breeze.” The conversation never escalates into anything approaching conflict and, as a consequence, there’s no real reason for it to be in the script.

Note as well how there’s nothing particularly fresh or surprising about it. We feel like we’ve heard this kind of script dialogue a million times before and this is another major symptom of just letting characters chat without defining why they’re talking.

In real life, people have these kinds of inconsequential conversations all the time, but they don’t belong in a screenplay in which dialogue should be a heightened reality as previously discussed.

Finally, there’s nothing to differentiate these characters from each other. Kalvin kind of has his own voice, but you could swap out Jay’s name for Dutch’s and Wally’s name for Jay’s and nobody would notice.

How to rectify this in your own script’s dialogue.

Go through your script highlighting one character’s dialogue at a time. Do they all sound the same? If so, it probably means you don’t know the characters as well as you could. But once you know them better, they’ll also begin to develop an individuality to the way they talk, what’s known as a “voice.”

Creating a “voice” with a character’s dialogue can definitely be tricky but it’s ultimately what makes them interesting: the way you show us who they are by how they talk and what they choose to talk about.

In Sex and the City, for example, we have four women who are all roughly the same age, live in the same city, come from similar backgrounds and all have good jobs, and yet each character’s dialogue has a “voice” because each one has a different worldview, attitude and outlook on life. And this comes out in what they choose to talk about and how they react to things.

Once you know your characters a little better in this way, then their dialogue will naturally begin to sound different because you will be able to write it according to their individual personalities.

Conclusion.

Writing easy-going “shooting the breeze” script dialogue is an easy trap to fall into. While there are no obvious glaring dialogue mistakes in these scenes and they’re competently written, this is actually half the problem.

It’s because this kind of genial, laid-back dialogue is so easy to write that it feels normal and safe and ends up becoming a default position for the whole script.

The trouble is, happy-go-lucky conversations are not particularly interesting to read and definitely not exciting to watch up on screen.

Another good way to eliminate screenplay dialogue that’s just “shooting the breeze” is to always remember that your characters’ speech should serve the needs of the scene, not the other way around.

In other words, script dialogue should not the be-all-and-end-all of a scene. It should be the last thing added to it—layered on top of the reason why the scene’s in the script in the first place—with stakes attached that relate back to the protagonist’s central dilemma.

The main purpose of a scene should be to push the story forward, from one beat to another. Therefore, the primary cause of bad script dialogue writing isn’t necessarily bad dialogue… It’s often a bad scene.

Maybe the scene itself needs work.

Great script dialogue depends on your characters being in an already great scene.

So if you want to know how to write good dialogue between your characters, the first step may be to take a look at your scenes and ramp up the stakes and conflict within them until there’s something emotionally interesting happening in each one—regardless of the dialogue.

If you can’t find a reason why, say, Abby and Monica’s conversation during a yoga class should be uncomfortable, difficult or revealing in some way, then it probably means the scene itself isn’t uncomfortable, difficult or revealing and can be cut.

Be ruthless when it comes to editing script dialogue. If your characters are having too easy a time of it during a conversation, it probably means you’re not putting them under enough duress in the script as a whole.

###

What techniques do you use to seek out bad script dialogue? What do you think of our suggestions to weed out and edit bad dialogue writing? We’d love to know in the comments section below.

Comments

Post a Comment