How to convey a character’s emotional state in scene description

How to convey a character’s emotional state in scene description?

So, as a director, I know not to tell actors to be a little angry here, or more happy there. This leads to generic responses in the acting, rather than specific, layered emotional responses.When you are writing, do you also want to avoid such language?ie. He stared at the door, angrily.

vs.

He glared at the door.

(pretty wack example, but w/e)I suppose its about adverbs.Anyways, when I write it out, it always seems pretty foolish, but the question comes back every time I think I’ve answered it for myself. In need of some clarification.

Lalithra, you raise a good question. On the one hand, there’s the adage about not writing anything in scene description that an actor can’t act and that the moviegoer can’t see — that basically the only thing we, as screenwriters, can include in scene description and parentheticals, is specific directions re a character’s actions. Unfortunately in working with actors, it’s preferable to describe the character’s emotional / psychological state, tied to what plot elements are impacting them at the moment, then allow the actor to translate that into action, as opposed to telling them specifically how to act.

Which is a big reason why the old adage — “only describe what a moviegoer can see” — isn’t a hard and fast rule. In a selling script, it’s almost as important, sometimes even more so to convey the mood and feeling of the moment rather than specific character actions.

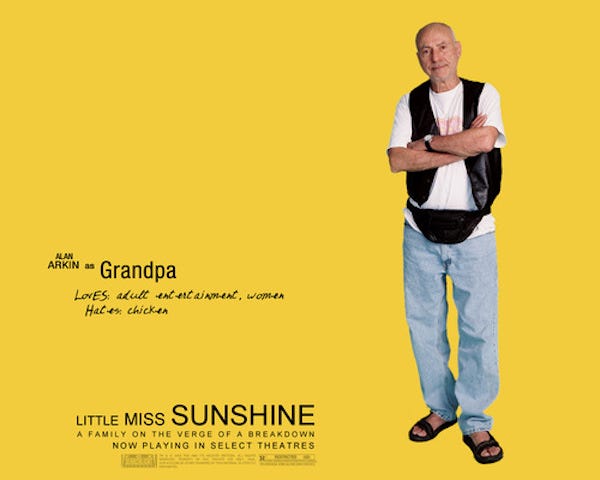

Let’s look at some examples from the wonderful script by Michael Arndt for Little Miss Sunshine. First, here is the introduction of Grandpa (P.4):

INT. BATHROOM - DAYTwo hands spill a brown powder onto a small mirror.A razor blade cuts the powder into lines.A rolled-up dollar bill lowers. The lies are snorted.The snorter lifts his head up. He is a short, chunky balding old man -- a Roz Chast kind of grandfather.This is GRANDPA, 80 years old.He sits down on the toilet seat, rubs his nose, takes a breath and relaxes as the drugs flood his system.

Very straight ahead description. Now let’s look at how Frank is introduced in the hospital after a failed suicide attempt (P. 3):

INT. HOSPITAL ROOM - DAYIn a wheelchair, parked against a wall, is Sheryl's brother, FRANK, also middle-aged. His wrists are wrapped in bandages.With empty eyes, he listens to the muted VOICE of the Doctor coming from the hallway.

With his “empty eyes,” the last line is a bit more about conveying Frank’s mood. This next example is even more ‘inside’ the character, Frank’s first moment in his new home — Dwayne’s room (P. 10):

Very unhappily, Frank enters the room and just stands there.SHERYL (cont'd) Thank you. I gotta start dinner. Come out when you're settled? And leave the door open. That's important. (beat) I'm glad you're here.She gives him a kiss on the cheek, then departs.Frank sits on the cot in his nephew's bedroom. On it is a Muppet sleeping bag with the Cookie Monster eating a cookie.Frank glances at the sleeping bag, then averts his eyes.This is pretty much the worst moment of his life.

“This is pretty much the worst moment of his life.” Not something a moviegoer could see. Not a description of a specific thing an actor can act. Rather going inside the character to convey to the reader (and the actor) what they’re feeling, the mood of the moment.

Arndt takes the same approach late in the script where Richard is seeing the other contestants at the pageant (P. 96):

The audience -- charmed -- starts clapping along. As she

finishes, the audience rises as one in a standing ovation.

Richard is the only one to remain seated. His face sinks as

reality finally hits him -- there's no way Olive will win.

“There’s ‘s no way Olive will win.” Again going inside the character to convey feeling and mood.

The reality is this: It is acceptable for a screenwriter to go beyond mere action description and write about the emotional status quo, even to go inside characters to reveal to the reader what they’re feeling. That said, a screenplay is not a novel, so we have to pick our spots. Best advice: Only go inside a character when you really want to drive home an important feeling, a key mood of the moment.

The reality is this: It is acceptable for a screenwriter to go beyond mere action description and write about the emotional status quo, even to go inside characters to reveal to the reader what they’re feeling. That said, a screenplay is not a novel, so we have to pick our spots. Best advice: Only go inside a character when you really want to drive home an important feeling, a key mood of the moment.

How To Accurately Write About Your Character’s Pain

The best thing about this online world of ours is you never know who you are going to meet. I don’t know about you, but one of the areas I struggle with is writing a character’s pain in a way that is raw, realistic…but not just “one-note.” So when I crossed paths with a paramedic-turned-writer, I got a little excited. And when she said she’d share her brain with us about the experience of pain, and how to write it authentically, I got A LOT excited. Read on, and make sure to visit Aunt Scripty’s links at the end. Her blog is full of more great medical info for writers.

Writing About Pain (Without Putting your Readers in Agony)

Pain is a fundamental part of the human experience, which means that it’s a fundamental part of storytelling. It’s the root of some of our best metaphors, our most elegant writing. Characters in fiction suffer, because their suffering mirrors our own.

Pain is a fundamental part of the human experience, which means that it’s a fundamental part of storytelling. It’s the root of some of our best metaphors, our most elegant writing. Characters in fiction suffer, because their suffering mirrors our own.

In good writing, physical suffering often mirrors emotional suffering. It heightens drama, raises the stakes, adds yet another hurdle for our hero to jump before they reach their glorious climax.

So why can reading about pain be so boring?

Consider the following (made-up) example:

The pain shot up her arm like fire. She cringed. It exploded in her head with a blinding whiteness. It made her dizzy. It made her reel. The pain was like needles that had been dipped in alcohol had been jammed through her skin, like her arm had been replaced with ice and electricity wired straight into her spine.

For your characters, at its worst the pain can be all-consuming. For your readers, though, it can become a grind. Let’s be honest, you gave up reading that paragraph by the third sentence.

In another story, a character breaks his ribs in one scene, then has, uhhh, intimate moments with his Special Someone in the next. Where did the agony go‽

There’s a fine line to walk between forgetting your character’s pain, elucidating it, and over-describing it.

So I’m here today to give you a pain scale to work with, and provide some pointers on how to keep in mind a character’s injuries without turning off your readers.

How Much Does It Hurt? A Pain Scale for Writers

Minor/Mild: This is pain that your character notices but doesn’t distract them. Consider words like pinch, sting, smart, stiffness.

Moderate: This is pain that distracts your character but doesn’t truly stop them. Consider words like ache, throb, distress, flare.

Severe: This is pain your character can’t ignore. It will stop them from doing much of anything. Consider words like agony, anguish, suffering, throes, torment, stabbing.

Obliterating: This is the kind of pain that prohibits anything else except being in pain (and doing anything to alleviate it). Consider words like ripping, tearing, writhing.

Metaphors, of course, are going to play somewhere on this spectrum, but I would suggest picking one level of pain and targeting it. For instance, don’t mix stinging with searing when finding a metaphor to build.

How Often Should We Remind Readers of a Character’s Pain?

Most pain that matters in fiction isn’t a one-and-done kind of a deal. A gunshot wound should burn and itch and ache as it heals. A broken bone should send a jarring blast of lightning into the brain if that bone is jostled or hit.

Most pain that matters in fiction isn’t a one-and-done kind of a deal. A gunshot wound should burn and itch and ache as it heals. A broken bone should send a jarring blast of lightning into the brain if that bone is jostled or hit.

Injuries need to have consequences. Otherwise, what’s the point?

There are three main ways to remind a reader of your character’s suffering: show them suffering, show them working around their suffering, and a third, more advanced, technique that I’ll mention in a moment.

If you want to show their pain, the easiest way is to tell: “her shoulder ached”; “she rubbed her aching shoulder”; “she rolled her shoulder subconsciously, trying to work out the aching stiffness” all convey what we want.

For frequency, try to limit those mentions to once per scene at the most, and perhaps as rarely as once per chapter.

However, we can choose something closer to the show route, by watching the character work around their injuries: “she opened the door awkwardly with her left hand to avoid the burn on her right”; “she led each step on the staircase with her good leg”; “Martin fiddled with his sling irritably”. That can be a little more frequent. It’s a reminder, but it’s also a small challenge that they’re solving before your very eyes. Huzzah!

One Final Technique: The Transmission of Agony

My best friend is a paramedic. She’s also had spinal fusion, has multiple slipped discs, and takes a boatload of pain medication. And yet I can see how much pain she’s in when we work together by the way she walks, talks, and carries herself.

Her pain isn’t constant. It changes. It ebbs and flows like the tide. It can be debilitating in one minute, bearable the next. So, too, can the agony of your characters:

“The agony had faded to a dull throb.”

“The pain in my shoulder ramped up the from stiffness all the way to searing, blinding agony faster than I could blink.”

“And, just when the pain was at its worst, it dissipated, like fog off some terrible lake.”

Go forth. Inflict suffering and woe upon your characters!

If I can offer one more piece of wisdom, it’s this: research the injury inflicted upon your character. At the very least, try to get a grasp on what their recovery might look like. It will add a level of realism to your writing that you simply can’t fake without it, and remind you that they should stay injured beyond the length of a scene.

Thank you for your time and your attention.

Comments

Post a Comment