Role of a Movie Narrator

Role of a Movie Narrator

Narration in movies has a very different function to voice over. The latter is an off screen voice rather than a character with dialogue. Voice overs have a direct message to the audience. The narrator has a more nuanced role in movies.

The simplest role of the narrator is exposition. They summarize key plot points so the movie can rapidly progress to the next scene and keep the story moving forward. Often narrated scenes are either difficult or too expensive to film individually, they contain too much story information and would make the film too long, and finally, narration harmonizes the story pacing and movie rhythms.

The secondary role of the narrator is more emotional, philosophical and spiritual. Narration in movies often explore greater themes and specificities in point of view which underpin the images on screen.

These are the key types of narrator:

FIRST PERSON NARRATOR

This style of narration reveals the inner most thoughts of the character speaking. It can be use to reveal secrets or that which should remain unspoken. First person narration can used to either directly address the audience and invite them to share the character’s point of view.

Alternatively, first person narration allows a character to reveal subtext or irony through what they say compared to what they really feel.

SECOND PERSON NARRATOR

This type of the narration is directed towards another character on the screen. It is an indirect communication between another character designed to highlight conflict and progress plot It is often more grounded in the story plot than greater themes.

THIRD PERSON NARRATOR (OMNISCIENT)

This perhaps, may be the most interesting form of narration. It has a similar function to the CHORUS of Ancient Greek plays. Third person narration explores the thematic content of the story with great wisdom and insight. It answers the central question of the film and reveals the point of the film.

Third party narration may also provide a social commentary and express a view that transcends the boundaries of the film. A third person narrator may even be God-like and poetic in their expression.

UNRELIABLE NARRATOR

An unreliable narrator has a purely disruptive role in movies. They serve to subvert the plot and audience viewpoint, often willingly, through deliberately misleading or outright lying to affect the story outcome.

Sometimes an unreliable narrator unknowingly alters the story course through misinformation or a flawed point of view or belief system.

Narration or voiceover is a stylistic device that is prone to abuse by covering up poor screenwriting, Use narration sparingly.

7 Reasons You Should Consider Adding Voice Narration to Your Film

Narration can be a powerful storytelling device for any film project. Here’s why you should consider adding it to yours.

There are probably a few films that I’ve seen over a hundred times. One of those is Bottle Rocket — Wes Anderson’s first feature starring Owen and Luke Wilson. I’ve also done a seriously unhealthy dive into how the film was made (based on the original short film) and how it came together.

At one point in its production, I’m 99.99% certain that they struggled with a draft of the script (or perhaps in the edit), and either James L. Brooks or L.M. Kit Carson (or any of the other many mentors or producers of the film) suggested narration as a cure-all.

It’s kind of odd how it comes into the film. It’s not set up from the beginning, but about halfway through, Anthony (one of the main characters) starts writing letters to his younger sister, which he reads aloud as narration. It really helps the film along, and it serves as a great way to keep things on track.

For filmmakers, narration is truly a powerful tool — from The Sandlot to The Matrix, we love to hear voice-over narration that helps us understand what we’re seeing. Regardless of where you are in production, here are seven reasons you too should consider using voice-over narration on your film project.

1. Beef Up Your Narrative

As with my theory behind Bottle Rocket, adding narration can be a great way to beef up your narrative. If you’ve done a draft of your screenplay (or even some preliminary filming) and find that one of your acts struggles, adding narration can be a great way to turn a section from a weakness into a strength.

2. Accelerate Exposition

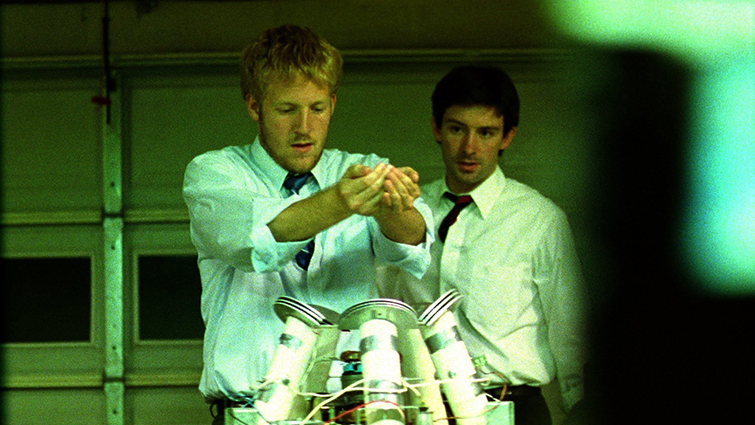

There are several examples of films hitting you hard and fast with voice-over narration. One recent example that comes to mind is Shane Carruth’s Sundance-winning Primer. While the plot is smart sci-fi that features some impressively researched time travel elements, the film is very simply shot and really benefits from voice-over narration that sets things up much more quickly than would otherwise be possible.

3. Add Depth to Your Character

Narration is also a great way to add depth to your character — or characters. Like The Wonder Years before it, The Sandlot is famous for its voice-over narration that explains the protagonist’s childhood summer scene-by-scene in the voice of an older version of the main character. Through his voice, we learn more about the character and how each of these scenes helped him develop into the successful (and clearly nostalgic) man he would eventually become.

4. Lay Out the Broad Strokes

One of my favorite examples of voice-over narration just straight going for it and explaining a film in big, broad strokes is Sarah Conner’s narration in Terminator 2. She very clearly lays out the events of the first film for the audience — and she brings you up to speed on all the relevant information about the film’s world right when you dive in. This happens more than you’d think with sequels, as it helps jump into the action right away without spending 30-45 minutes gradually catching the audience up.

5. Make Your Film More Active

Not that the great filmmaker Quentin Tarantino needs much help making his films active and fun, but his dual Kill Bill films are just another trick of the trade that Tarantino implements to great fun and effect. While she is never named in the film, Uma Thurman’s “The Bride” offers voice-over narration throughout the two films to go along with record scratch freeze frames and stylized VFX, seemingly just for the fun of it.

6. Add Humor to Your Scenes

Similarly to making your films more active, adding voice-over narration can also add more humor to your scenes. This may be a more subtle example, but I’ve seen Badlands by Terrence Malick almost as many times as Bottle Rocket, and I still crack up at Sissy Spacek’s voice-over narration, in which she alternates between describing the most mundane actions (which we subsequently see carried out on-screen) and some of the most poignant notes about humanity (which Martin Sheen’s Kit demonstrates).

7. Issues of Reliability

If you are looking to add narration to your project, it’s also worth considering making it less than reliable. Notable in recent years in jarring examples like Fight Club and, later, Mr. Robot, the unreliable narrator can cause a very drastic thematic response when the truth is revealed to the audience. An almost-textbook example however would have to be David Fincher’s Gone Girl, in which we dive deep into just how unreliable a narrator can be.

The Role of the Narrator

One of the most far-reaching decisions an author must make is how to narrate the story. Or: Who is telling the story to whom under which circumstances?

While not a traditional archetype, and in many cases not even a participating character, the narrator is never really quite the same entity as the author either.

To begin with the basics, the standard narrator types are:

- first-person, where usually the protagonist tells his or her own story

- third-person limited, where a narrator tells a story from one character’s point of view only, meaning that the audience/reader is not told of any events that this character is unaware of

- third-person omniscient, where the narrator can relate what any of the characters are doing and thinking, and is not limited in what to present to the audience/reader

In film, first person and third-person limited effectively amount to the same thing: the audience gets one person’s perspective on the story per shot or scene (there is also the first-person “point of view” camera angle, but rarely is an entire film presented that way). In prose, first and third person is the difference between “I did this” and “she (or he) did that”. This is a stylistic choice. In the sense of what the narrator knows and tells, there is not necessarily much difference.

Close or Distant

But potentially there is big difference between narrative stance. A narrator who is limited to reporting in third person on only one character can do so “close” or “from a distance”. In the former, the narrator tends to remain neutral, reporting without explicit commentary. The reader is immersed in the mind and experience of the character.

“From a distance” narration is a sort of birds-eye view of the goings on in both space and time, and it may bestow upon the narrator a greater awareness, allowing him or her to comment on or display an attitude towards the character who is trapped in level of plot and interaction with other characters. This style was common in novels of the nineteenth century, and still today most voice-overs by narrators in movies work like this.

The difference between close and from a distance holds for an omniscient narrator too. A close all-seeing and all-knowing narrator can jump to any character at will. If the author decides to allow the narrator to comment, then that narrator takes on a personality of his or her own, and may even be a character in his or her own right, perhaps to the extent of taking part in the action at some point. A famous example of this technique is John Fowles’ The French Lieutenant’s Woman.

So, the type of narrator determines the degree of discrepancy of awareness between the narrator and the characters. Furthermore, if the narrator has a personality, then it follows that she has an agenda, her own motivations, and perhaps the desire to manipulate the way the reader feels about the characters or the story. This manipulation may become part of the fiction, so that the author’s intention is that the ideal reader sees through the attempts of the narrator-character to skew the understanding of the audience. Or perhaps the narrator’s memory may simply be faulty. Either way, one speaks of “unreliable narrators” if they are not to be trusted.

The Act of Telling as Fiction

Instead of just writing, many authors picture the situation of the story being told. In the case of a novel, what kind of a text is this supposed to be? Why were these words set onto paper? If there is a definite answer, then there is a narrator figure with some kind of personality and the text becomes part of the fiction. So the author may choose whether to reveal what sort of text it is that the narrator is ostensibly fabricating, i.e. what the reader is reading (or the viewer is watching). A first-person novel may take the form of a certain text type, for example of a journal, which determines the tense the narrator uses and the narrator’s awareness. The text type may be clearly named, as in William Boyd’s Any Human Heart (diary), or it may only be revealed later, as in Nabokov’s Lolita (defence plea).

In a first-person story, the narrator can know more than the character (i.e. him or herself) if the narrator is relating a story with the benefit of hindsight, for example as an old person talking about his or her own youth.

Coding and Decoding

It can be satisfying for the audience, though possibly more because of the thrill of solving a puzzle than through the effects of the story, when an author forces the audience to decode what the narrator tells. For instance by restricting the narrator to reporting only a character’s particular point of view. If the character doesn’t understand what’s going on, and the narrator does not explain it, the audience might get it anyway.

Benjy in The Sound And The Fury watches them hitting, hitting, and it takes the reader a while to figure out that Benjy is watching men play a game of golf, but does not have the words to describe it. Similarly in William Goldings The Inheritors, prehistoric Lok for the first time in his life meets a person from another tribe, who holds out a stick to him that shrinks at both ends. Suddenly the tree next to Lok sprouts a branch. Lok has never seen bow and arrow before, and therefore does not understand that he was just shot at, let alone have the words to describe it. The reader, after a bit of decoding, understands more than the protagonist.

Implicit in all this are the following “people” involved in the act of producing and consuming a story:

- Author

- Narrator

- Ideal Reader/Viewer (who understands everything the author is trying to achieve)

- Real Reader/Viewer (who may not be paying that much attention …)

Comments

Post a Comment