The French Connection (1971)

The French Connection (1971)

New York City cop Doyle and his partner are trying to bust a drug cartel based in France. Albeit short-tempered, Doyle is a dedicated cop whose nemesis, Alain Charnier, is too polished for a criminal.

The French Connection is a 1971 American action-thriller film[6] directed by William Friedkin. The screenplay, written by Ernest Tidyman, is based on Robin Moore's 1969 non-fiction book The French Connection. It tells the story of New York Police Department detectives Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle and Buddy "Cloudy" Russo, whose real-life counterparts were Narcotics Detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso, in pursuit of wealthy French heroin smuggler Alain Charnier. The film stars Gene Hackman as Popeye, Roy Scheider as Cloudy, and Fernando Rey as Charnier. Tony Lo Bianco and Marcel Bozzuffi also star. The Three Degrees are featured in a nightclub scene.

At the 44th Academy Awards, it won the Oscars for Best Picture, Best Actor (Hackman), Best Director (Friedkin), Best Film Editing, and Best Adapted Screenplay (Tidyman). It was nominated for Best Supporting Actor (Scheider), Best Cinematography and Best Sound Mixing. Tidyman also received a Golden Globe Award nomination, a Writers Guild of America Award and an Edgar Award for his screenplay. A sequel, French Connection II, followed in 1975 with Gene Hackman and Fernando Rey reprising their roles.

The American Film Institute included the film in its list of the best American films in 1998 and again in 2007. In 2005 the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Plot[edit]

In Marseille, an undercover police detective follows Alain Charnier, who runs the world's largest heroin-smuggling syndicate. The policeman is assassinated by Charnier's hitman, Pierre Nicoli. Charnier plans to smuggle $32 million worth of heroin into the United States by hiding it in the car of his unsuspecting friend, television personality Henri Devereaux, who is traveling to New York City by ship.

In New York City, detectives Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle and Buddy "Cloudy" Russo go out for drinks at the Copacabana. Popeye notices Salvatore "Sal" Boca and his young wife, Angie, entertaining mobsters involved in narcotics. They tail the couple and establish a link between the Bocas and lawyer Joel Weinstock, who is part of the narcotics underworld.

Popeye learns from an informant that a massive shipment of heroin will arrive in the next two weeks. The detectives convince their supervisor to wiretap the Bocas' phones. Popeye and Cloudy are joined by federal agents Mulderig and Klein.

Devereaux's vehicle arrives in New York City. Boca is impatient to make the purchase—reflecting Charnier's desire to return to France as soon as possible—while Weinstock, with more experience in smuggling, urges patience, knowing Boca's phone is tapped and that they are being investigated.

Charnier realizes he is being observed. He "makes" Popeye and escapes on a departing subway shuttle. To avoid being tailed, he has Boca meet him in Washington D.C., where Boca asks for a delay to avoid the police. Charnier, however, wants to conclude the deal quickly. On the flight back to New York City, Nicoli offers to kill Popeye, but Charnier objects, knowing that Popeye would be replaced by another policeman. Nicoli insists, however, saying they will be back in France before a replacement is assigned.

Soon after, Nicoli attempts to shoot Popeye but misses. Popeye chases Nicoli, who boards an elevated train. Popeye commandeers a car and gives chase. Realizing he is being pursued, Nicoli works his way forward through the carriages, shoots a policeman who tries to intervene and hijacks the motorman at gunpoint, forcing him to drive straight through the next station, also shooting the train conductor. The motorman passes out and they are just about to slam into a stationary train when an emergency trackside brake engages, hurling the assassin against a glass window. Popeye arrives to see the killer descending from the platform. When the killer sees Popeye, he turns to run but is shot dead by Popeye.

After a lengthy stakeout, Popeye impounds Devereaux's Lincoln Continental. He and his team take it apart searching for the drugs, but come up empty-handed. Cloudy notes that the vehicle's shipping weight is 120 pounds over its listed manufacturer's weight. They remove the rocker panels and discover the heroin concealed therein. The police restore the car to its original condition and return it to Devereaux, who delivers the Lincoln Continental to Charnier.

Charnier drives to an old factory on Wards Island to meet Weinstock and deliver the drugs. After Charnier has the rocker panels removed, Weinstock's chemist tests one of the bags and confirms its quality. Charnier removes the drugs and hides the money, concealing it beneath the rocker panels of another car purchased at an auction of junk cars, which he will take back to France. Charnier and Sal drive off in the Lincoln, but hit a roadblock with a large contingent of police led by Popeye. The police chase the Lincoln back to the factory, where Boca is killed during a shootout while most of the other criminals surrender.

Charnier escapes into the warehouse with Popeye and Cloudy in pursuit. Popeye sees a shadowy figure in the distance and opens fire a split-second after shouting a warning, killing Mulderig. Undaunted, Popeye tells Cloudy that he will get Charnier. After reloading his gun, Popeye runs into another room and a single gunshot is heard.

Title cards note that Weinstock was indicted but his case dismissed for "lack of proper evidence"; Angie Boca received a suspended sentence for an unspecified misdemeanor; Lou Boca received a reduced sentence; Devereaux served four years in a federal penitentiary for conspiracy; and Charnier was never caught. Popeye and Cloudy were transferred out of the narcotics division and reassigned.

"The French Connection" is routinely included, along with "Bullitt," "Diva" and "Raiders of the Lost Ark," on the short list of movies with the greatest chase scenes of all time. What is not always remembered is what a good movie it is apart from the chase scene. It featured a great early Gene Hackman performance that won an Academy Award, and it also won Oscars for best picture, direction, screenplay and editing.

The movie is all surface, movement, violence and suspense. Only one of the characters really emerges into three dimensions: Popeye Doyle Gene Hackman, a New York narc who is vicious, obsessed and a little mad. The other characters don't emerge because there's no time for them to emerge. Things are happening too fast.

The story line hardly matters. It involves a $32 million shipment of high-grade heroin smuggled from Marseilles to New York hidden in a Lincoln Continental. A complicated deal is set up between the French people, an American money man and the Mafia. Doyle, a tough cop with a shaky reputation who busts a lot of street junkies, needs a big win to keep his career together. He stumbles on the heroin deal and pursues it with a single-minded ferocity that is frankly amoral. He isn't after the smugglers because they're breaking the law; he's after them because his job consumes him.

Director William Friedkin constructed "The French Connection" so surely that it left audiences stunned. And I don't mean that as a reviewer's cliché: It is literally true. In a sense, the whole movie is a chase. It opens with a shot of a French detective keeping the Continental under surveillance, and from then on the smugglers and the law officers are endlessly circling and sniffing each other. It's just that the chase speeds up sometimes, as in the celebrated car-train sequence.

In "Bullitt," two cars and two drivers were matched against each other at fairly equal odds. In Friedkin's chase, the cop has to weave through city traffic at 70 m.p.h. to keep up with a train that has a clear track: The odds are off-balance. And when the train's motorman dies and the train is without a driver, the chase gets even spookier: A man is matched against a machine that cannot understand risk or fear. This makes the chase psychologically more scary, in addition to everything it has going for it visually.

The movie was shot during a cold and gray New York winter, and it has a doomed, gritty look. The landscape is a waste land, and the characters are hardly alive. They move out of habit and compulsion, long after ordinary human feelings have lost the power to move them. Doyle himself is a bad cop, by ordinary standards; he harasses and brutalizes people, he is a racist, he endangers innocent people during the chase scene (which is a high-speed ego trip). But he survives. He wins, too, but that hardly matters. "The French Connection" is as amoral as its hero, as violent, as obsessed and as frightening.

The French Connection: shock of the old

William Friedkin's 1971 thriller set in New York is nihilistic, unapologetic and even racist. But it still feels contemporary

This year, as every year, there have been some big anniversary rereleases. The 1981 Ivan Passer movie Cutter's Way has just been dusted off, Kubrick's 1971 classic A Clockwork Orange was treated to a big retrospective showcase at Cannes this year, soon Basil Dearden's Victim (1961) is to be revived at BFI Southbank in London as part of a Dirk Bogarde season, and Alain Resnais's Last Year in Marienbad (1961) has resurfaced.

I staged my own "anniversary" rewatching this week of a movie I hadn't seen in many years: the last time was on TV decades ago. It is William Friedkin's The French Connection, now 40 years old, based on a true story, and starring Gene Hackman as detective Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle, a driven New York cop who wears a hat that makes him look like some sort of hip jazz musician and whose intuitive street sense allows him to nose out the secret players in a colossal heroin import operation, bringing the drugs into New York from Marseille.

What an experience it is to see it again, a movie whose vivid evocation of New York bears comparison to Scorsese but which I now realise I remember chiefly from one single scene. The gangsters employ a "Chemist" – a small role comparable to the gun-dealing "Easy Andy" from Scorsese's Taxi Driver. This is a smart-mouthed, bespectacled individual whose job is to test the drugs before they buy, and is by implication paid from the wares themselves. He uses a complex chemical kit including a thermometer in which the mercury rises with the purity. (Is that kit genuine? Or did Friedkin dream it up?) "Eighty-nine percent pure junk," the Chemist finally pronounces, "if the rest is like this, you'll be dealing on this load for two years."

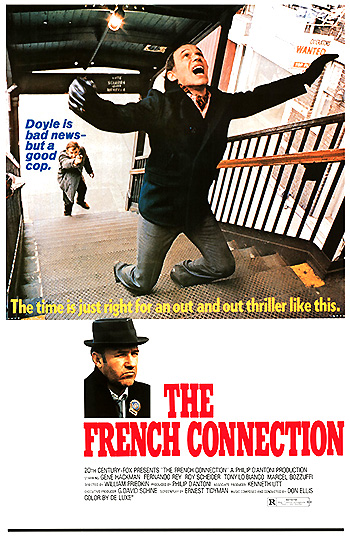

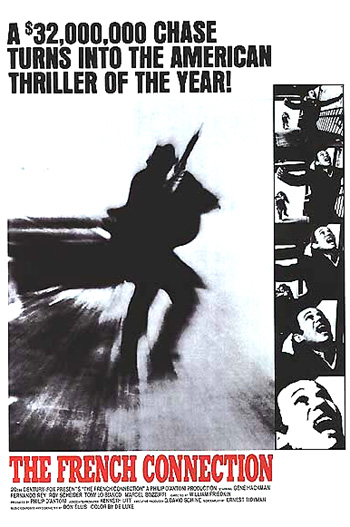

To watch The French Connection now is to experience the shock of the old: a lost world of the city, and a lost style of film-making. For a start, there is that poster image taken from the climax of the famous subway v car chase – Doyle shoots someone in the back as the man reaches the stop of a staircase, and his grimacing victim flings his arms out at the moment of death. It is a distinctive image, but eccentric, asymmetric, and utterly anti-heroic: the hero? The guy indistinctly in the background? And he's shooting someone in the back? Surely not! It's the sort of image that would never get used as a film poster today. A poster for The French Connection now would have the faces of Hackman and his partner Russo (Roy Scheider) sweatily to the fore, with a gun or two, and the automobiles in the background.

In the opening reel, the movie socks us with another scene that could never happen in 2011, or not without a multitude of ironising tics to deflect its potential for offence. Popeye and Russo storm into a black bar and harangue and slap around the customers, demanding answers. And when Popeye gets back to the station house, he drops the N bomb. The modern audience nervously asks itself: where is the black police chief to balance this? The black judge? Or maybe a black cop whose tough integrity and professionalism Doyle can come, finally, apologetically, to respect? Nowhere.

In one scene, Doyle and Russo take their suspect and give him a brutal working over in one of New York's vacant lots – a feature of the era – burnt out waste-grounds, sometimes large, that Tom Wolfe in his 1987 novel Bonfire of the Vanities called urban "gloamings" and which Malcolm Gladwell, in the chapter on broken-window theories in his 2000 book The Tipping Point, said were the key breeding grounds for crime.

A modern Hollywood action thriller like this would need to show redemption for Doyle. For example, the precise explanation for his nickname would be an opportunity for some gentle backstory comedy, and meet the all-important need for him to be a sympathetic character. Not in 1971. His name is Popeye. That's it.

One of his resentful colleagues, nettled at the chief's indulgence of Doyle, furiously remarks that these hunches of Doyle's once got a good cop killed. Again – a modern audience, schooled in modern screenplay verities, is primed for a big revelation somewhere before the big finale. Who was this good cop? Does Doyle, for all his bluster, feel desperately guilty? Will nailing the "French Connection" bad guys make up for it and bring Doyle redemption? Er, not exactly: the final moments of The French Connection are a powerful, even magnificent repudiation of the modern piety of redemption and sympathy. It is a stunningly nihilist ending, one to set alongside Polanski's Chinatown.

Perhaps most striking of all is the leisured, unhurried pace of The French Connection. It is fully one hour before gunshots are fired. There are many scenes in which Doyle simply cruises around New York, searching, brooding; these, to me, evoke the city as powerfully as Mean Streets or Taxi Driver. The details are lovingly recorded: sometimes it seems as if we are watching a documentary by the Maysles brothers. And the ghostly, ambient honk of car horns, sometimes fluttering a little on the soundtrack, say 1971 like nothing else.

Having said that, a lot of The French Connection feels contemporary. The long surveillance scenes, in which we watch the shadowy mobster coming in and out of his "front" operation – a low-rent diner – accompanied by Doyle's mumbling speculative commentary, anticipates the modern world of police work, as well as Hackman's own role in Coppola's The Conversation. And in their rackety, prehistoric way, Doyle and Russo look like the forebears of McNulty and Bunk in The Wire. Moreover, watching The French Connection again brings home to you how much the movie influenced James Gray's dramas The Yards (1999) and We Own the Night (2007).

This weekend, you could do a lot worse than get the DVD out and treat yourself to your own special 40-years-on rerelease of The French Connection.

News is under threat ...

… just when we need it the most. Millions of readers around the world are flocking to the Guardian in search of honest, authoritative, fact-based reporting that can help them understand the biggest challenge we have faced in our lifetime. But at this crucial moment, news organisations are facing an unprecedented existential challenge. As businesses everywhere feel the pinch, the advertising revenue that has long helped sustain our journalism continues to plummet. We need your help to fill the gap.

You’ve read in the last six months. We believe every one of us deserves equal access to quality news and measured explanation. So, unlike many others, we made a different choice: to keep Guardian journalism open for all, regardless of where they live or what they can afford to pay. This would not be possible without financial contributions from our readers, who now support our work from 180 countries around the world.

We have upheld our editorial independence in the face of the disintegration of traditional media – with social platforms giving rise to misinformation, the seemingly unstoppable rise of big tech and independent voices being squashed by commercial ownership. The Guardian’s independence means we can set our own agenda and voice our own opinions. Our journalism is free from commercial and political bias – never influenced by billionaire owners or shareholders. This makes us different. It means we can challenge the powerful without fear and give a voice to those less heard.

Synopsis

THE FRENCH CONNECTION, 1971, 20th Century Fox, 104 min. Dir. William Friedkin. Arguably the greatest American crime film ever made. Gene Hackman stars as Detective Popeye Doyle, who’s muscling minor hoods in NYC when he catches the trail of a huge shipment of French heroin. With partner Roy Scheider, Hackman dogs drug kingpin Fernando Rey through the concrete jungle - highlighted by a brain-jangling car chase that still hasn’t been topped. THE DRIVER, 1978, Fox, 90 min. Dir. Walter Hill. An extremely tough, pared-to-the-bone noir, vastly underrated on its initial release, THE DRIVER pits existential getaway driver Ryan O’Neal against pitbull detective Bruce Dern in a cat-and-mouse pursuit through the wasted underbelly of mid-’70s Los Angeles. Walter Hill’s homage to Jean-Pierre Melville and the Euro crime film offers amazing car chases and, in her first Hollywood film, Isabelle Adjani.

14 Fascinating Facts About The French Connection

Gene Hackman, William Friedkin, Roy Scheider, Eddie Egan, and Randy Jurgensen in The French Connection (1971).

UNIVERSAL HOME ENTERTAINMENT

00:30

01:00

In 1970, producer Philip D’Antoni and director William Friedkin set out to make a film based on the true story of one of the biggest drug busts in America history. They battled through studio rejection, casting drama, and a book that Friedkin couldn’t even get through to produce what became one of the most iconic crime thrillers of all time.

The French Connection won five Academy Awards, including Best Pictures, after its 1971 release, and still stands as one of the greatest films of the 1970s because of its gritty visual style, powerhouse performances, and one of the greatest car chase sequences ever put on film. Here are 14 facts about the making of The French Connection, from its roots to its release.

1. THE REAL DETECTIVES ARE IN THE MOVIE.

The French Connection is an adaptation of Robin Moore’s book of the same name, which was itself the true story of one of the biggest drug busts in American history, led by NYPD detectives Eddie Egan and Sonny Grosso in the early 1960s. Egan and Grosso remained close to the story throughout its development, and when the time came to actually make the film, they were both part of the process. Director William Friedkin kept them on-set almost every day as technical advisors, and even cast them in the film. Egan, the basis for “Popeye” Doyle, plays Doyle and Russo’s supervisor, Walt Simonson, which meant he got a chance to play his own boss. Grosso, the basis for “Cloudy” Russo, plays Clyde Klein, one of the two federal agents assigned to assist the detectives on the case.

Though Friedkin later recalled that the detectives thought his filmed version of events was fairly accurate, the director also noted that the film is an “impression” of the real case. In reality, the drug bust at the heart of The French Connection took several months to develop, and never involved a high-speed chase or a shootout.

2. WILLIAM FRIEDKIN WASN’T A FAN OF THE BOOK.

Wiliam Friedkin directs Linda Blair on the set of The Exorcist (1973).

ALAN BAND/KEYSTONE/GETTY IMAGES

Robin Moore’s book The French Connection eventually found its way into the hands of Philip D’Antoni, a producer who was then fresh off the success of his first feature film, Bullitt. D’Antoni was taken by the story of these two New York cops with very different personalities who’d managed to pull off an amazing drug bust, and wanted to find the right director to make the gritty kind of drama he imagined. For that, he turned to William Friedkin, who recalled D’Antoni was particularly interested in him because of his background as a documentary filmmaker. D’Antoni and Friedkin went to New York to meet Egan and Grosso, and Friedkin saw the potential for a great film in their story. What he didn’t see, though, was the appeal of Moore’s book, which he claimed years later that he never actually finished.

“I never read Robin Moore’s book," Friedkin said. "I tried to. I don’t know how many pages I got through, not many. I couldn’t read it, I couldn’t follow it.”

3. THE FRENCH CONNECTION WAS TURNED DOWN BY ALMOST EVERY STUDIO.

In early 1969, D’Antoni managed to set up The French Connection at National General Pictures, seemingly cementing backing for the film. Within a few months, though, things fell apart after D’Antoni reportedly said the budget for the film would be $4.5 million, something National General tried to retract with a later statement. National General then dropped the film, leaving D’Antoni and eventually Friedkin on the hunt for another studio. It wasn’t easy.

"This film was turned down twice by literally every studio in town,” Friedkin recalled. “Then Dick Zanuck, who was running 20th Century Fox, said to me, 'Look, I've got a million and a half bucks tucked away in a drawer here. If you can do this picture for that, go ahead. I don't really know what the hell it is, but I have a hunch it's something.'"

So, Friedkin and D’Antoni made The French Connection at Fox for Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown. Ironically, by the time the film was released, internal stress about the studio’s trajectory meant that Zanuck and Brown had both been let go from the studio, and Brown later recalled that they could only see the film if they bought a ticket for it like everyone else.

4. WILLIAM FRIEDKIN PARTICIPATED IN DRUG BUSTS.

Though Friedkin wasn’t necessarily that interested in the narrative as laid out by Robin Moore’s book, he was very interested in the actual street-level day-to-day existence of a narcotics detective in New York City. Taken by Egan and Grosso, Friedkin wanted to get an up close view of how the two detectives worked, and arranged frequent ride-alongs with them for both himself and his eventual stars, Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider. As the director later recalled, these trips were often about much more than observing.

“In fact, the scene where they come in, bust up a bar and grab all the stuff, I saw that three, four nights a week,” Friedkin recalled. “Usually Eddie Egan, who was the character who Hackman played, he would give me his gun in a situation like that. He would say, 'Here, watch the back.' And I would be standing in the back with a .38 and he did that with Hackman and Scheider and they got to know what it was like to do a frisk properly. Gene and Roy improvised that scene from having seen what Eddie and Sonny [Grosso] did."

5. GENE HACKMAN WAS NOT THE FIRST CHOICE FOR POPEYE DOYLE.

When it came time to cast the brash detective “Popeye” Doyle, D’Antoni and Brown were gravitating toward Gene Hackman, then best known for films like I Never Sang for My Father. Zanuck was interested, but Friedkin was not.

“I instantly thought it was a bad idea,” Friedkin recalled.

At Zanuck’s urging, Friedkin had lunch with Hackman, and while the actor recalled it being a nice time, Friedkin later said he almost “fell asleep” during their first meeting. The film’s police advisors, including Grosso, were also skeptical of Hackman, and Hackman himself later recalled that Egan had wanted Rod Taylor to play the character based on him, because he thought they looked alike.

Friedkin, meanwhile, had his own ideas about who should play Popeye. He wanted Jackie Gleason, but Gleason’s last film at Fox was a financial failure and the studio wasn’t interested. Then he considered columnist Jimmy Breslin, but Breslin refused to drive a car and, it soon became clear, wasn’t exactly a natural actor. Eventually, with no convincing backup actor “in the bullpen,” D’Antoni issued an ultimatum to his director: Cast Hackman, or risk losing the production window on The French Connection.

“I said ‘Phil, you wanna do this with Hackman, I don’t believe in it, but I’ll do it with you,’” Friedkin recalled. “’We’ll give it our best shot.’”

Hackman won the 1972 Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance as Popeye Doyle.

6. FERNANDO REY WAS CAST BECAUSE OF A MIXUP.

To cast much of The French Connection, Friedkin came to rely on a “character around New York” named Robert Weiner. It was Weiner who initially brought Roy Scheider, who was cast without even auditioning, to Friedkin’s attention.

When it came to time to cast someone to play the French drug kingpin Alain Charnier, Friedkin went to Weiner and said “let’s get that French guy that was in Belle de Jour. What the hell’s his name?”

Weiner called Friedkin back and told him the actor he was thinking of was named Fernando Rey, and said Rey was available. Friedkin signed Rey, sight unseen, then went to pick him up at the airport when he arrived in New York. When the two men finally met face-to-face, Friedkin realized that, while he did recognize Rey, he was not the actor he’d been thinking of. Friedkin had really wanted Francisco Rabal. Instead, he was faced with Rey, who wouldn’t shave his goatee and noted that, as a Spanish actor, his French was not especially good.

"Rabal, it turned out, was unavailable and did not speak one word of English. So we went with Gene Hackman, who I didn't want, in one lead, and Fernando Rey, who I didn't want, in the other," Friedkin later recalled.

7. WILLIAM FRIEDKIN TRIED TO “INDUCE” A DOCUMENTARY FEEL.

Because he was taken by the street-level feel of The French Connection’s story, Friedkin wanted to infuse a sense of “induced documentary” into his film by making it look as often as possible like the camera operators just happened to witness two cops working the streets of New York. This was achieved, in part, by searching for the most authentic locations possible, but it was also achieved by never choreographing the film’s shots.

“In order to do that, from time to time, I would not rehearse the actors and the camera crew together,” Friedkin recalled. “I rehearsed them separately.”

That meant that, while the camera operators often knew what would happen in any given scene, they didn’t know exactly how it would happen, leaving them to capture Hackman and Scheider’s performances on the fly.

8. THE “POUGHKEEPSIE” DIALOGUE WAS A REAL INTERROGATION TECHNIQUE.

In keeping with the film’s documentary feel, much of the dialogue in The French Connection turned out to be improvised based on the situations in each scene. Because Egan and Grosso were often on-set as technical advisors, they were able to frequently offer up real phrases and words they might have used in the same situations. According to Friedkin and Grosso, this included Popeye’s famous “Did you ever pick your feet in Poughkeepsie?” dialogue.

“Yeah, that was a thing Eddie used to do that would drive me crazy,” Grosso recalled, “and when Billy wanted to do it in the movie I prayed to God, tried to talk him out of it.”

According to Friedkin and Hackman, Egan devised the “pick your feet in Poughkeepsie” phrase as a deliberate non sequitir to throw off interrogation subjects while Grosso would ask more straightforward, legitimate questions.

“It means nothing,” Friedkin recalled.

9. GENE HACKMAN STRUGGLED WITH PLAYING POPEYE.

Though he’d been the producer’s choice for the role and was eager to get it right, Hackman found the time he spent on the set of The French Connection with Eddie Egan—the basis for Popeye Doyle—difficult, calling the veteran cop “insensitive.” Hackman’s discomfort with Egan’s own personality was compounded by the fact that he had to use a number of racial slurs, including the N-word, as part of his dialogue. Hackman expressed his concern about saying the words to Friedkin, who told him it was part of the movie and he had to say it.

“I just had to kind of suck it up and do the dialogue,” Hackman recalled.

According to Scheider, Hackman’s reservations also stemmed in part from his quest to make Popeye seem like a relatable character, when Friedkin saw him as a rough, brash cop who was willing to do whatever it took to solve the case.

“Gene kept trying to find a way to make the guy human ... and Billy kept saying ‘No, he’s a son of bitch. He’s no good, he’s a prick,'" Scheider said.

10. THERE WAS TENSION BETWEEN GENE HACKMAN AND WILLIAM FRIEDKIN.

Already saddled with a star he hadn’t wanted to cast in the first place, Friedkin became convinced that Hackman didn’t necessarily possess the savagery necessary to commit 100 percent to playing Popeye Doyle. He decided that, as a director, the best thing he could do would be to push Hackman to get him “crazy” on a daily basis.

“I decided to make myself his antagonist, and I had to light a fire under him every day,” Friedkin said.

This sense of antagonism came to a head while shooting the scene in which Doyle and Russo stand outside eating pizza in the cold while surveilling Charnier, who’s eating in a nice French restaurant. Friedkin wanted to shoot a close-up of Hackman’s hand as he rubbed them together, to indicate just how cold the two men were, and he demonstrated how he wanted Hackman to rub his hands. Hackman, displeased with Friedkin’s tone, decided to antagonize him right back and pretend that he didn’t understand exactly what Friedkin was looking for. The exchange got so heated that Hackman finally demanded that Friedkin step in front of the camera and demonstrate exactly what he should be doing with his hands. Friedkin did, and when they were done with the close-up, Hackman was done with work.

“And he walked off the set for the rest of the day,” Friedkin recalled.

11. THE FRENCH CONNECTION’S FAMOUS CAR CHASE WAS SHOT WITHOUT PERMITS.

The French Connection is perhaps best remembered today for its iconic chase sequence, in which Popeye Doyle commandeers a car to pursue Nicoli, Charnier’s chief enforcer, who’s commandeered an L train overhead. It’s a thrilling sequence, and it began with a conversation between Friedkin and D’Antoni as they walked the streets of New York City, spitballing ideas. D’Antoni demanded that whatever chase they came up with be better than the already legendary chase his previous film, Bullitt, had featured, and together the two men hit upon the idea that it shouldn’t be two cars, but rather a car and a train.

To get permission to use the correct train for the sequence, Friedkin recalled giving a New York transit official “$40,000 and a one-way ticket to Jamaica,” because the official was certain he’d be fired for allowing them to shoot the sequence. The rest of the chase, including all the dynamic work with the car under the train tracks, was shot without permits. Friedkin used assistant directors, with the help of off-duty police officers, to clear out traffic on the blocks ahead of the shoot, but they were not always entirely successful. At least one of the crashes in the finished film was a real accident, not a planned stunt.

12. THE CAR CHASE ALMOST DIDN’T WORK.

The now-legendary chase scene in The French Connection was shot over the course of five weeks, with the shoot divided between time on the train and in the car and working around New York rush hour schedules. Even after all that work, though, Friedkin was concerned about the footage. After reviewing it, he realized it just wasn’t as “exciting” as he’d hoped it would be, and expressed that concern to stunt driver Bill Hickman.

As Friedkin later recalled at an Academy screening of the film, Hickman responded: “Put the car out there under the L tracks tomorrow morning at eight o’clock. You get in the car with me and I’ll show you some driving.”

The next day, Hickman—who was also a stunt driver in Bullitt—got in the car with Friedkin, who mounted one camera in the passenger seat and operated a second one himself from the backseat. According to the director, Hickman drove 26 blocks under the Stillwell Avenue L tracks at speeds of up to 90 mph, with only a police “gumball” light on top of the car to warn people what was coming. That gave Friedkin the extra speed and excitement he needed to complete the sequence.

13. THE FRENCH CONNECTION’S TITLE WAS ALMOST CHANGED.

After all the casting drama and the cold shooting days and the high tension of the chase sequence, The French Connection finally entered post-production and was nearing completion when, according to D’Antoni, Fox’s promotional department sent him a memo declaring their intention to change the title. In the documentary The Poughkeepsie Shuffle, D’Antoni didn’t explain why the studio ultimately retracted that idea, but he did note that alternate titles for the film included Doyle and Popeye, both attempts to play up the tough cop at the center of the story.

14. WILLIAM FRIEDKIN DOESN’T KNOW WHAT THE ENDING MEANS.

Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider in The French Connection (1971).

UNIVERSAL HOME VIDEO

The French Connection’s ending is almost as famous as its chase scene, though not quite. The film seems to be ending happily for the cops, as they’re able to capture many of the people behind the heroin shipment, but Doyle isn’t satisfied with that. He pursues Charnier into the bowels of an abandoned building, determined to catch him, and is so jumpy that he very nearly fires on Russo when he sees him. Then, upon a seeing a shadowy figure in the distance, Popeye fires several times, only to discover the man was not Charnier, but one of the two federal agents helping them with the case. Unfazed and still determined, Popeye heads off into the darkness, still in pursuit, and we hear a single gunshot ring out. The title cards at the end of the film tell us that Popeye didn’t actually catch Charnier, so who was he shooting at? According to Friedkin, it’s a deliberately ambiguous moment to leave audiences wondering.

“People have asked me through the years what [that gunshot] meant. It doesn’t mean anything ... although it might,” the director said. “It might mean that this guy is so over the top at that point that he’s shooting at shadows.”

| The French Connection (1971) | |

Background  The French Connection (1971) is director William Friedkin's brilliant, fast-paced, brutally-realistic police/crime film - his commercial break-through film ("The time is just right for an out and out thriller like this"). The true-to-life film about the largest narcotics seizure of all time in 1962 - with an innovative semi-documentary-style technique that conveys the story with very few words, was produced by Phillip D'Antoni who had made the exciting police film Bullitt (1968). The French Connection (1971) is director William Friedkin's brilliant, fast-paced, brutally-realistic police/crime film - his commercial break-through film ("The time is just right for an out and out thriller like this"). The true-to-life film about the largest narcotics seizure of all time in 1962 - with an innovative semi-documentary-style technique that conveys the story with very few words, was produced by Phillip D'Antoni who had made the exciting police film Bullitt (1968).The police thriller features an unsympathetic protagonist - the vulgar, brutal, tireless, unlikable, maniacal and sadistic Jimmy "Popeye" Doyle (Gene Hackman) as the main undercover New York City narcotics cop, who toes the thin line between fighting crime and committing crimes himself. He passionately and obsessively pursues drug pushers with his partner Buddy "Cloudy" Russo (Roy Scheider). One of the film's posters emphasized: "Doyle is bad news - but a good cop."The film's raw script was based on Robin Moore's best-selling book of the same name about the ruthless, real-life adventures of idiosyncratic Harlem special narcotics squad officers Eddie Egan (the Doyle character) and Sonny Grosso (the Russo character) - both have small cameo roles in the film and served as technical advisers for the film. The heavily-nominated film (with eight nominations) was a multiple-Academy Award winning effort, taking accolades in five categories: Best Director (William Friedkin), Best Actor (Hackman with his first Oscar), Best Adapted Screenplay (Ernest Tidyman), Best Editing (Jerry Greenberg), and Best Picture. The three other nominations included: Best Supporting Actor (Roy Scheider), Best Cinematography (Owen Roizman), and Best Sound. The authenticity of the film is accentuated by dozens of sordid, on-location NYC sets (the Lower East Side, Times Square, Bedford-Stuyvesant, and Grand Central Station, among others), sub-titles for the French dialogue, rough "Egan-style" police work, brutal winter scenes in the city, hand-held camera shots, and gutsy, nitty-gritty performances. The film inspired a complementary sequel four years later - French Connection II (1975), directed by John Frankenheimer. The Story The dramatic opening scene shows two simultaneous actions many miles apart. In Marseilles, France, a malevolent professional hit man Pierre Nicoli (Marcel Bozzuffi) kills a French detective with a bloody gunblast to the face. The assassin callously tears off a piece of the man's long loaf of French bread. And in Brooklyn, New York during the Christmas holiday season, a street Santa Claus figure (Doyle in disguise) and a hot dog vendor (Buddy in disguise) chase down a knife-wielding dope pusher named Willy (Alan Weeks). Using the tactic of good cop/bad cop, they drag the two-bit drug dealer to a vacant lot and intimidate him without finding any drugs on him. Typical of his obscene vocabulary, sadistic nature and strong-arm tactics, Doyle grills the suspect with his famous pet non-sequitur: When's the last time you picked your feet, Willy? Who's your connection Willy? What's his name?...I've got a man in Poughkeepsie who wants to talk to you. You ever been to Poughkeepsie? Huh? Have you ever been to Poughkeepsie?After work, Doyle and Russo (posing as plainclothesmen) share a drink at an Eastside club and stumble into a suspicious group of "greasers" at a corner table: "That table is definitely wrong," surmises Doyle. They see large sums of money being flashed by a handsomely-dressed playboy ("the last of the big spenders") named Sal Boca (Tony Lo Bianco) and his wife Angie (Arlene Farber). "Just for fun," Doyle suggests tailing "the greaser with the blonde." Taking the long-shot hunch, they trail the couple until 7 am the next morning, witness a drug "drop," and learn that Boca is a small-time candy/newspaper store owner (at "Sal & Angie's"). The French criminal mastermind behind drug shipments to New York is a Marseilles-based, debonair international criminal Alain Charnier (Spanish actor Fernando Rey) - his associate is hit man Pierre Nicoli The Story (continued)  After more surveillance, the two narcotics detectives soon learn that the Boca's small business couldn't support their lavish lifestyle (their business is only a "front"), and that they both have a suspicious history of criminal activities: After more surveillance, the two narcotics detectives soon learn that the Boca's small business couldn't support their lavish lifestyle (their business is only a "front"), and that they both have a suspicious history of criminal activities:Our friend's name is Boca, Salvatore Boca. B-O-C-A. They call him Sal. He's a sweetheart. He was picked up on suspicion of armed robbery. Now get this. Three years ago, he tries to hold up Tiffany's on Fifth Avenue in broad daylight. He could have got two and a half to five. But Tiffany's wouldn't prosecute. Also, downtown, they're pretty sure he pulled off a contract on a guy named DeMarco... (Angie) - She's a fast filly. She drew a suspended for shop-lifting a year ago. She's only a kid - nineteen according to the marriage license...hmmm, nineteen going on fifty...He's had the store a year and a half. Takes in a fast seven grand a year...So what's he doin' with two cars and hundred dollar tabs at the Shea?...The LTD's in his wife's name. The Comet belongs to his brother, Lou [Benny Marino]. He's a trainee at the garbageman's school on Wards Island. He did time a couple of years ago. Assault and robbery.Sal eventually leads them to the Manhattan apartment of his Jewish drug kingpin Joel Weinstock (Harold Gary), a wealthy financial backer of illicit drug importation into the country. In a shakedown in a sleazy bar, Popeye announces: "Popeye's here," forces the patrons into a lineup against the wall, watches pill containers drop to the floor, and grills another suspect: "Do you pick your feet?" As he cleans the bottom-side of the bar counter of drugs, he quizzically asks: "What is this? A f--kin' hospital here? Huh?" From one of his informants (Al Fann), Doyle learns the reason why everyone's clean and there are no hard drugs on the streets: "Ain't nothin' around...There's been some talk...- a shipment, comin' in this week, the week after. Everybody's gonna get well." Because his hunches have "backfired" before, Popeye is denied permission by his boss Lieutenant Walter Simonson (Eddie Egan) to work on his current hunches about Boca and Weinstock: "Big score, my ass. At best, he's sellin' nickel and dime bags." But they plead with Simonson to get a court order to allow them two wiretaps ("one on the store, one on the house") and to continue their pursuit in a special assignment: Buddy: We got the information there's no s--t on the street, right? It's like a god-damn desert full of junkies out there. Everybody waiting to get well.In Marseilles, the crafty Charnier stashed heroin into the specially-designed Lincoln Continental Mark III car of French TV celebrity/star Henri Devereaux (Frederic de Pasquale) who unwittingly escorts the shipment to New York. [Coincidentally, a month before the film opened, a drug stash of 230 lbs. of heroin was intercepted in a car on a boat from France.] Two other federal agents, Mulderig (Bill Hickman) and Klein (Sonny Grosso) are also assigned to follow up on the case and join the pursuit, but Mulderig is an old nemesis of Popeye's. Russo and Doyle, the two nattily-dressed, overworked, uneducated New York street cops attempt to bring to justice the French drug smuggling ring. As the two supercops trail their "French connection" suspects through Manhattan, they must eat cold pizza out in the cold as the two smugglers dine in the warmth of a fancy restaurant. In a richly-appointed suite in the Westbury Hotel while testing the quality of the heroin in front of Boca and Weinstock, the chemist (Pat McDermott) watches the rising thermometer: Blast off - one eight O.The two Americans discuss a deal with the French drug syndicate for a half-million dollar buy of the shipment of 60 kilos of heroin from the French foreign market - a deal worth $32 million on the street. The experienced Weinstock exercises caution toward the fidgety, impulsive Boca, the Brooklyn contact: "This is your first major league game, Sal. One thing I learned. Move calmly, move cautiously. You'll never be sorry." When Charnier arrives in New York, he immediately senses that he is being trailed by Doyle. Popeye attempts to discreetly follow Charnier through the underground subway system. Doyle phones into his FBI colleague Mulderig: "This is Doyle. I'm sittin' on Frog One." The clever, suave Frenchman with a silver-handled umbrella outwits Doyle, smugly waving goodbye through the departing subway train window. Having been identified, Popeye becomes a prime target for elimination. Charnier's hired, murderous sniper Pierre Nicoli ("Frog Two") muffs his attempt to kill Doyle, and is pursued in an exciting, pulsating and brilliant car-train chase sequence through Bensonhurst, Brooklyn. In one of the best pursuits ever put on film [rivaling the producer's previous car-chase scene in the film Bullitt - and the reason the film was awarded an Oscar for Best Editing], Doyle flags down and hijacks a motorist's Pontiac Le Mans (for a "police emergency") and pursues the drug dealer on board the out-of-control, run-away elevated commuter subway train (where he has terrorized passengers, killed the train's cop and conductor, and caused the motorman to have a heart-attack). He weaves in and out of traffic and track supports at top speed through the streets of New York below, barely missing a mother and baby carriage at one point, while driving with one eye on the street and one eye on the train above. At the end of the chase after a climactic train crash [photographed with the train moving away from the camera - and then reversed], Nicoli escapes from the wreckage, believing that he is free of Doyle. But Doyle guns him down at the top of the train depot stairs - the image became the famous promotional still used to advertise the film on posters. After a search of Devereaux's car turns up nothing, Buddy deduces that the car is 120 lbs overweight - he insists that the car still conceals the heroin shipment. The bags of white powder are found hidden in the rocker panels. When the car is returned intact to Devereaux, the heroin deal is allowed to continue. In the finale as the police close in on the criminals on Wards Island following the heroin deal, there is a massive ambush and shoot-out. The film concludes with Boca's killing and Weinstock's arrest. As Doyle and Buddy pursue their prey through a subterranean warehouse on Wards Island, Mulderig is accidentally killed by Doyle. The perturbed and frustrated cop is relentlessly obsessive in his search for the elusive Charnier (who evidently slipped away and was never caught): The son of a bitch is here. I saw him. I'm gonna get him.The film deliberately concludes on a mysterious note - what actually happens is ambiguous and open to varying interpretations. Doyle runs off through the warehouse to further pursue his prey. A single shot is heard - off-screen - before the film abruptly ends with a black screen. [Note: The film literally ends with a 'bang.'] Subtitles, presented about a still photo of each criminal, explain the failed denouement: JOEL WEINSTOCK was indicted by a Grand Jury. Case dismissed for "lack of proper evidence." |

Comments

Post a Comment